States increasingly offering health care coverage for immigrants, noncitizens

Gabriel Henao fled Colombia to escape a guerrilla group who, he said, twice threatened to kill him. After some time in Mexico, he arrived in Colorado in July 2022, settling in Fort Collins.

His severe stomach pain started when he was in Mexico, he said. It was debilitating and left him bedridden for days at a time. The pain continued to plague Henao in the United States, but he said he didn’t make enough money cleaning houses to pay for health insurance.

Colorado did not offer Medicaid coverage to residents living in the country without legal status such as Henao, or to immigrants in the mandatory five-year waiting period after receiving their green cards. Without coverage, Henao couldn’t get a proper checkup, he said, let alone a diagnosis or treatment for his stomach pain.

That changed at the beginning of this month, when Henao received care through Colorado’s OmniSalud program, which provides health care coverage to low-income immigrants in the country without documentation. When the program started accepting enrollments in 2022 it covered 10,000 people without requiring them to pay premiums, and this year Colorado expanded the number of zero-premium slots to 11,000.

Alianza NORCO, a nonprofit organization that supports immigrants in northern Colorado with legal and other resources, is helping Henao acclimate to the U.S. and assisted with his application to the OmniSalud program.

“I started to get really scared, nervous, anxious because I didn’t have money to care for my health,” said Henao, 44, a father of three who owned a clothing warehouse in Colombia. He has applied for asylum, saying his life was in danger in his native country.

Now, after undergoing an appendectomy three weeks ago, “I feel excellent,” he said in Spanish through a translator provided by the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition.

Colorado is one of a growing number of Democratic-dominated states that are extending health care coverage to a limited number of immigrants who otherwise wouldn’t be eligible for public insurance because of their legal status.

Supporters say such programs save money in the long run, because insured people are more likely to receive treatment for chronic conditions and get preventive care, thereby avoiding expensive medical crises that end up costing taxpayers and raising premiums for the insured. But as more states face budget crunches, critics object to spending millions to insure people who are living here without authorization.

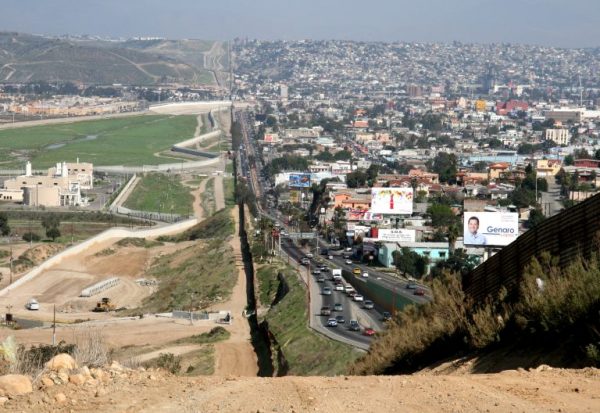

Meanwhile, the flood of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border figures to be a major issue in the presidential campaign. And earlier this week, nine Democratic governors sent a letter to the Biden administration and congressional leaders urging them to solve the “humanitarian crisis” of “the sustained arrival of individuals seeking asylum and requiring shelter and assistance.”

The Colorado program serves immigrants, regardless of their legal status, who have an income of less than $22,000 a year for an individual or less than $45,000 for a family of four. The state filled its 11,000 available slots in two days. The program costs the state an estimated $73 million annually, according to the Colorado Division of Insurance.

“For some people, it’s the first time that anyone in their family has been able to have health care, which is a huge, life-changing advancement,” said Raquel Lane-Arellano, communications manager for the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition. “They’re not just seeking emergency care. They’re able to go get preventative care.”

Covering more people

Advocates say the pandemic, and the health disparities it revealed, prompted state efforts to provide coverage to more people, regardless of their immigration status.

“It’s a very exciting trend that we are monitoring very closely. Some of the work on this has been decades long,” said Tanya Broder, senior staff attorney at the National Immigration Law Center. “But the recognition of the value of investing in health care for all really increased during the height of the pandemic, when states recognized that our health is interconnected, and it makes sense to protect the health of everyone in the community in order to protect public health.”

California, Oregon and Washington state also offer health care coverage to people of all ages who have incomes below a certain level, regardless of their immigration status. Minnesota will do so starting in 2025.

In addition, at least 24 states and Washington, D.C., now offer coverage to pregnant immigrant women who are in the five-year waiting period to qualify for Medicaid, according to an analysis by KFF, a health care policy research organization. Meanwhile, seven states — California, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Rhode Island and Washington — use state dollars or money from the state-federal Children’s Health Insurance Program, known as CHIP, to offer coverage for a year postpartum regardless of immigration status, according to KFF.

Starting in March, Michigan will eliminate the five-year waiting period for Medicaid for children and pregnant women. The change will result in coverage for up to 4,000 children and about 5,500 women, most of them Hispanic, said Simon Marshall-Shah, senior policy analyst for the Michigan League for Public Policy. Michigan will spend about $6.4 million on the program, but federal matching funds will bring the total to $26.4 million.

And this month, a new law went into effect in California offering Medicaid coverage to adults ages 26 to 49 regardless of immigration status.

California rolled out its health care coverage for immigrants in phases. In 2020, the state expanded its Medicaid program, which it calls Medi-Cal, to young adult immigrants ages 19 to 25, modeling the Young Adult Expansion program after a previous one for children under 19.

“This expansion comes out of our state general fund, meaning there isn’t like a new tax or a new funding source that we have to raise for this expansion,” said Sarah Dar, California Immigrant Policy Center’s policy director. Since emergency room visits are costly to both individuals and hospital systems, creating programs that expand access to primary health care coverage “makes good fiscal sense,” she said.

Pushback on efforts

But critics say California can’t afford the expansion amid the state’s mounting budget deficit. Republican state Sen. Brian Jones, who is the minority leader, released a statement earlier this month urging Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom to enact an 18-month freeze on the program.

“In the midst of a significant budget deficit, hospitals shutting down, and a massive influx of migrants illegally crossing our open border, now is not the time to be expanding this costly government program,” Jones wrote. “Our priority should be safeguarding critical services and core functionalities.”

In Nevada, Republicans blocked efforts to expand Medicaid to immigrants without documentation last year, saying the proposal would be too costly. During a March floor debate, Republican state Sen. Robin Titus, who is also a physician, said she worried about adding thousands more to the Medicaid rolls when the state already struggles with a lack of enough health practitioners.

“You’re diluting an even more diluted system. So, in the long run, it might hurt everyone,” she said. “How do you solve that access to care when you already don’t have enough of us?”

However, Republican-dominated Utah this month began enrolling kids in a new state-funded children’s health insurance program that covers immigrant children without documentation. The bipartisan bill signed by Utah Republican Gov. Spencer Cox last March allocated $4.5 million toward the program.

Critics say immigrants who are living in the United States illegally burden the system without contributing to it. But even unauthorized workers have payroll taxes deducted from their paychecks, and they pay sales taxes on their purchases. Immigrants without legal status pay property taxes on their homes or indirectly as renters, and at least half file income tax returns.

Those taxes help support public insurance programs such as Medicaid and Medicare, research shows. An analysis published in 2022 in the American Medical Association’s JAMA Network Open by researchers from Boston University, Harvard Medical School and others found immigrants here without legal permission pay an estimated $51.9 billion more into the health care system than the cost of their care.

Ultimately, “it’s about values,” said Dar, of the California Immigrant Policy Center. “We want our communities to be healthy. … It costs much less to just get preventative care, get regular checkups, get on insulin; if you need it, get on a statin, if you’ve got blood pressure issues. Those things are actually far, far cheaper than expensive life-saving procedures and tests.”

Starting this month in Washington state, immigrants without documentation and recipients of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which delays deportation of immigrants who came to the U.S. as children, are allowed to shop for health plans through the state’s exchange marketplace. Those making $36,450 or less can qualify for state aid to help them cover premiums.

In July, the state also will launch a new Medicaid program that will cover poorer residents ages 19 and older, though there will a spending cap.

Dr. Leo Sergio Morales, who co-directs the University of Washington’s Latino Center For Health, noted that certain treatments and procedures, such as transplants, are especially costly and increasingly inaccessible for the uninsured.

“Transplants can be life-saving,” Morales said, “[and] people have to be able to afford the medications and treatment that follows the transplant — so, a lifetime of immunosuppression.”

States are also grappling with budget constraints. Illinois, for example, last November paused new enrollments for its health care coverage program for noncitizens 42 and older.

Colorado’s OmniSalud now provides zero-premium coverage to 11,000 people, but the state has about 200,000 immigrants who are in the country without authorization, Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition’s Lane-Arellano noted. “The biggest thing we want to see is the program continuing to expand,” she said. “This is very much that ‘all ships rise’ kind of situation.”

“There are economic reasons and sound data that prove preventative care saves the state of the economy and families in the long run,” she added. “It hurts families, and it hurts our entire community, our economy, when people get sick or are forced into medical debt.”

Henao hopes more states create programs like OmniSalud.

“It will be positive for all communities if immigrants who are arriving are able to get the support that they need, are able to get the ability to work, have access to health insurance,” he said. “Medical care is costly in this country.”

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on Stateline, which is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: info@stateline.org. Follow Stateline on Facebook and Twitter.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login