Western Rail Coalition looks to revive passenger rail service on long-dormant line connecting Colorado mountain towns

Passengers or petroleum products? That’s one of the key questions being bandied about in a renewed effort to revive part of the long-dormant Tennessee Pass rail line linking southern Colorado to the state’s Western Slope.

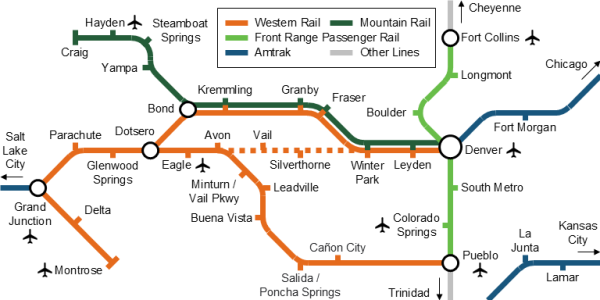

As the Polis administration continues to focus almost exclusively on planning for passenger rail in the northern Front Range and the northern mountains between Denver and Craig, some rail advocates, experts and elected officials are urging the state to study the out-of-service Union Pacific rail line between Pueblo and western Eagle County that last saw freight trains in 1997.

In late October, members of the recently formed Western Rail Coalition fired off a letter to Gov. Jared Polis and the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) requesting the state conduct a service development plan (SDP) for light-rail-style passenger service on the Tennessee Pass line between Glenwood Springs and Leadville, connecting to the Eagle County Regional Airport.

CDOT this month is expected to complete an SDP for passenger service on Union Pacific’s active Central Corridor (or Moffat) line between Denver and Bond, where trains would then head north to Steamboat Springs and Craig, with a possible Yampa Valley Regional Airport link in Hayden.

Dubbed “Mountain Rail”, that proposed project received a recent boost as the state reached a new deal with Union Pacificthat provides for three free roundtrip passenger train trips a day in exchange for the rail giant using and maintaining the state-owned Moffat Tunnel free of charge. The previous 99-year lease deal charging UP $12,000 a year expired on Jan. 6, and the new 25-year lease is set to be finalized in May after a temporary extension.

Class I railroads such as Omaha-based Union Pacific charge passenger services up to $20 a train mile to use their tracks, and the Denver-to-Craig rail route is approximately 465 miles roundtrip.

UP is looking to replace lost coal-train traffic as coal-fired power plants in Craig and Hayden shut down, and the newly proposed lease deal with its three additional roundtrip trains a day doesn’t include existing passenger service on Amtrak’s daily California Zephyr between Chicago and California’s Bay Area, the popular Winter Park Express Ski Train or the seasonal Rocky Mountaineer tourist train to Moab, all of which pay fees to use UP’s Colorado tracks.

The impetus for Mountain Rail is to ease traffic on U.S. Highway 40 and connect workers in lower-cost housing in Craig, Hayden, Kremmling and Granby with resort areas in Steamboat Springs and Winter Park, while also providing a ski train connection backed by Alterra Mountain Company, which owns Steamboat and runs Winter Park for the city and county of Denver.

Residents of Eagle County, which sued to stop an expansion of Utah oil-train traffic – a case that was recently heard by the U.S. Supreme Court – were concerned Utah’s oil boom could spill over onto the out-of-service Tennessee Pass line. A more direct route to Gulf Coast refineries, the line connects with UP’s active Central Corridor line at Dotsero in western Eagle County.

Part of that concern stemmed from the attempt by Union Pacific to expedite a lease deal with Texas short-line operator Rio Grande Pacific Corp., which initially had been tabbed to operate the proposed 88-mile Uinta Basin Railway project that would connect Utah’s northeastern oil fields with UP’s main rail line near Price, Utah.

Judges dismissed Eagle County’s concerns over the revival of the Tennessee Pass line but agreed the Uinta Basin Railway needed more environmental scrutiny, which is what the Supreme Court is now weighing. In the meantime, Rio Grande Pacific is no longer involved in the Uinta Basin Railway.

Western Rail Coalition’s James Flattum, a finance professional and “advocate for all things transit in Colorado,” said the Eagle Valley Passenger Rail proposal between Glenwood and Leadville, which could eventually connect on through to Pueblo, would be one of two reasons heavy freight rail traffic, including oil trains, won’t return to the line that travels over Tennessee Pass near Ski Cooper and along the Arkansas River.

“The biggest thing that will prevent the Tennessee Pass line from ever returning as a through-freight route is the severely steep grade, which is prohibitively expensive for modern freight railroads to operate over,” Flattum said of the 3% grades. “This is the main reason why the line was taken out of service back in 1997, and remained out of service even during multi-year periods of exceptionally high oil prices and sustained demand for energy transport.”

The Tennessee Pass line was taken out of service but never officially abandoned following the merger of Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads in 1996. Other than the Central Corridor line through the Moffat Tunnel, it’s the only other rail route through the Colorado Rockies.

“From a Colorado state perspective, using the [Tennessee Pass] line for a separate purpose, such as transporting people instead of oil or coal, is the most effective thing that can be done to make the corridor even less attractive for freight companies to resume service on. The steep grades are much less of a problem for operating lighter, quieter, and lower-emission passenger trains.”

CDOT officials, focused first and foremost on both Mountain Rail planning and the Front Range Passenger Rail (FRPR) proposal between Fort Collins and Pueblo, declined to go on the record on the Eagle Valley proposal, but in the past CDOT has expressed an interest in acquiring the Tennessee Pass line if UP makes it available. CDOT officials say they take their direction from the governor’s office but did include the possibility of revived passenger and freight service on the line in the agency’s recently revised Colorado Freight and Passenger Rail Plan.

The state highway agency is looking for alternatives to increasingly congested and difficult-to-maintain mountain highways and sees an airport-linked train in Eagle County as a possible boon to resort workers and tourists. In 2021, an agricultural landowner in southern Colorado tried to acquire the Tennessee Pass line from UP, offering to pay for Pueblo-to-Minturn passenger rail. That led to UP’s lease deal with Rio Grande Pacific that the company remains interested in.

But CDOT officials made it clear they are currently prioritizing Mountain Rail and FRPR and would need to see more local support, alignment and planning along the Tennessee Pass line to move forward.

The Western Rail Coalition estimates reviving the dormant Tennessee Pass line between just the Eagle County Regional Airport and Avon would cost around $200 million, while Glenwood to Leadville would cost $400 million on the high end, which is less than CDOT’s ongoing Floyd Hill project on I-70. Colorado Mountain Rail is still short on detail at this point, but proponents put the cost at under $100 million from Denver to Craig because the line is fully active.

By comparison, the most bare-bones version of Front Range Passenger Rail from Fort Collins to Pueblo will cost $3.2 billion, and higher-end versions could cost as much $8 billion. The FRPR will seek public funding in the form of a sales tax ballot question, and the Colorado Legislature last session passed several other forms of potential rail funding.

The administration of Colorado Gov. Jared Polis has set lofty goals to get people out of cars and onto other forms of transportation. Asked to comment on the WRC proposal to revive the Tennessee Pass line that last saw passenger trains in the 1960s, Polis’ office emailed this statement via spokesperson Eric Maruyama:

“Gov. Polis rolled out Transportation Vision 2035 which calls for Colorado to double down on transit and passenger rail to create a larger network of transportation options that save Coloradans time and money, reduce traffic, and protect our air, which includes Front Range Passenger Rail from Pueblo to Fort Collins and Mountain Rail from Denver to Winter Park to Steamboat Springs. These ambitious unprecedented proposals have widespread support from local communities along the route and any additional routes would need to demonstrate that same level of local support.”

The Western Rail Coalition letter was signed by Holy Cross Energy President and CEO Bryan Hannegan, former Eagle County Commissioner Kathy Chandler-Henry, Walking Mountain Science Center founder and former Vail Mayor Kim Langmaid, former Avon Mayor Amy Phillips and current Avon Mayor Tamra Nottingham Underwood – all of whom signed on as individuals, not representatives of their various organizations.

Recently reelected Eagle County Commissioner Matt Scherr confirmed the county is moving ahead with towns along the line on a “request for participation on a western rail task force to the towns and CORE Transit [the regional transportation authority formed in 2022], then the group will select a chair.” The idea is to explore with the state the possibility of revived passenger rail on the Tennessee Pass line.

While the Rio Grande Pacific lease on the line is between Sage (a railroad point near the Eagle County Regional Airport in Gypsum) and Parkdale, just west of the Royal Gorge, the WRC advocates are pushing to study an initial phase of Glenwood to Leadville on the line – a scenic route that would run through Glenwood Canyon to the state’s highest mountains near Leadville. It would also run near ski areas from Sunlight to Vail/Beaver Creek to Ski Cooper.

Asked about the proposal and its potential to block future heavy freight traffic, Leadville Mayor Dane Greene said, “That’s maybe the only point that makes sense to me.” Greene said a straight-shot, light-rail-style train in the I-70 corridor, with town commercial cores, bus terminals and gondolas up into the mountains that are right along the railroad tracks – which is the case in both Glenwood and Avon — makes more sense both for tourists and workers.

“If we’re interested in moving people in a more effective way and trying to keep them out of individual vehicles, there might be a more benefit to actually improving the bus line,” Greene said. “Just from a practical standpoint, if people are going to spend a lot of money, that would be more cost-efficient and probably would enjoy greater use.”

Greene points out the rail line passes about four miles from downtown Leadville and goes through a tunnel at Tennessee Pass, making it difficult to connect to Ski Cooper, which is owned by Lake County.

At the other end of the proposed line, current council member and former Glenwood Springs Mayor Jonathan Godes fully favors more passenger rail service over any increase in heavy freight trains carrying hazardous materials.

“We love Amtrak in Glenwood, so passenger rail, at least as far as Glenwood is concerned, up through the [Eagle County Regional] airport to wherever, sounds great,” said Godes, an outspoken opponent of increased oil-train traffic through his Colorado River community.

“We’re here because of the rail; our town developed because of the rail,” Godes said. “And I look at a place where there’s literally a junction [of two rail lines] at Dotsero … and you know what they have that we don’t …? They have a lot of land.” Godes thinks dense affordable housing near multimodal transit hubs could serve workers in both Eagle and Garfield Counties, where Glenwood is located.

Eagle County Regional Airport Director David Reid, whose facility has been booming – in part because of the endless traffic snarls on I-70 – said a rail connection could be ideal, depending on the details.

“Any time you can make your airport multimodal, it is just more functional if there’s more redundancy or more aspects to the transportation part of it,” said Reid, whose facility is looking to add an international terminal. “It would improve potentially just the accessibility, not just to the airport, but to the whole region here. EGE being central in the Rockies, we’re a central airport to the Roaring Fork Valley, the west side of the state, the east side of the state going up north. So I think [rail] would feed into that concept and idea anyway.”

Peter Rickershauser, a retired rail executive in Denver who worked for Southern Pacific and briefly for Union Pacific before being recruited away to competing Class 1 freight carrier Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) to head up network development, points to Aspen’s conversion of its rail line to Glenwood to a bike trail as a missed mass-transit opportunity.

“The point is it’s not necessarily what makes sense now. It’s what makes sense in the future,” said Rickershauser, whose first job at BNSF was implementation of the UP/SP merger settlement agreements that mothballed the Tennessee Pass line. “So, before people generally accept letting a rail corridor disappear, recognize this: It will be gone forever and people should rue the day when they say, ‘Gosh we should have hung onto that.’”

Rickershauser views rail connections to airports as vital to Colorado’s future.

“When we talk about connections to the airport, if people agree with the concept that travelers are going to gravitate to the easiest path, then it is easy to get off a plane and onto a train, or off a train and onto a plane, and that’s going to be what they want to do,” Rickershauser said.

Editor’s note: A version of this story first appeared in the Colorado Springs Gazette.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login