Backcountry skiing closures ill-advised, unenforceable in wake of tragic avalanche deaths

The Jan. 7 avalanche in the East Vail Chutes that tragically claimed the life of Tony Seibert (CAIC photo).

You really can’t put the genie back in the bottle, even if the genie is 900 feet wide, 1,500 feet long, 10 feet deep and deadly as hell.

The Jan. 7 avalanche in the East Vail Chutes that killed Tony Seibert – the grandson of Vail founder Pete Seibert – was the eighth deadly slide in the area since 1986, according to Denver Post writer and longtime Vail Valley resident Scott Willoughby.

That’s a terrible number, and way too many deaths in a backcountry area that grows in popularity every year and is easily accessed through a gate at the top of Vail Mountain. The slide also has triggered talk of a U.S. Forest Service closure there.

But, as Willoughby wrote in the Post last week, “You can’t close the Colorado backcountry just because it’s winter.”

In fact, I would take that step farther and say, “You can’t change the backcountry culture or end the booming backcountry industry that’s developed over the past two decades – an industry ski resorts have helped build.” In other words, you can’t put the genie back in the bottle.

When I first moved to Vail in 1991 we would get calls at the Vail Daily from the Vail Associates PR people asking us not to print certain pictures. Pictures of skiers or snowboarders catching inverted air. Pictures of anyone riding deep powder in the backcountry.

Now part of ski industry marketing includes showing kids upside down in halfpipes and terrain parks. Blue Sky Basin is billed as having a bit of a backcountry feel, with glades of trees left intact and cliff bands ripe for the hucking. And, of course, there are backcountry and side-country gates all over the place.

Part of that evolution over the last 25 years was the realization that the Forest Service, which owns the land on which most of the nation’s ski resorts operate, is inadequately staffed and funded to stem the tide of backcountry enthusiasts ranging farther and wider to find untracked snow. Nor does the federal government particularly think it has the right to prevent people from using their own public lands.

Meanwhile, law enforcement officials would prefer to focus on traffic safety, property crimes, assaults and public drunkenness in the ski towns at the base of the mountains. That left rope cutting up to the ski patrol in the 1980s and 90s, and – understandably so – I think most patrollers would prefer to help people injured inbounds.

In the 1990s, most U.S. ski resorts, in conjunction with the Forest Service, went to a more European-style, ski-at-your-own risk model – warning snow riders about the dangers and educating them about avoiding avalanche danger – but generally waving the white flag in the losing war on out-of-bounds snow riding.

Since that time there’s been a GoPro-fueled explosion in backcountry ski and snowboard travel, and trying to close the gates now would lead to Prohibition-style bootlegging not seen since the days of the Jackson Hole Air Force.

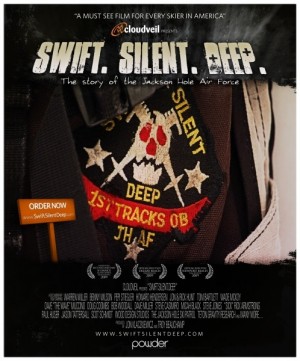

That group of renegade riders, including the late Doug Coombs, waged a guerilla-style campaign against Jackson’s occasionally overzealous ski patrol that ultimately ended in Coombs being ostracized and the ski area finally relenting to mounting pressure. The exploits of the JHAF are chronicled in the movie “Swift. Silent. Deep.”

I wrote a story about that film back in 2007 (re-posted below), but the Adventure Journal’s Steve Casimiro did the definitive piece in 2010. Casimiro, who’s had a lot of experience with backcountry skiing death and destruction, does a very eloquent job of defending the risks while urging people to limit their exposure, and he’s no fan of glorifying pure luck in the backcountry.

But the bottom line is we’re all here to inject our lives with some degree of risk. Otherwise we’d all be back in a cubicle in the big city.

You will, however, steadily dial back the risk as you get older, get married, have kids. And if you’ve ever been in an avalanche and survived (as I was on Monarch Pass back in the 80s), you’ll never look at an unbroken 40-degree pitch of perfect powder quite the same way.

I like what’s going in Vail these days with the ski patrol conducting periodic avalanche safety seminars — call (970) 754-4610 or check out Vail Ski Patrol on Facebook at www.facebook.com/vail.skipatrol — and now a new avalanche education series offered by Apex Mountain School (970-949-9111).

Such educational solutions, and the continued and hopefully increased support of the Colorado Avalanche Information Center remain the only way to sensibly deal with mounting backcountry carnage.

And here’s the piece I did back in 2007 on “Swift. Silent. Deep.” – a film about the Jackson Hole Air Force, which was a renegade backcountry group somewhat akin to the aerialist Ravinos that were run off Vail Mountain in the 1980s:

Into the wild blue yonder

Antics of the Jackson Hole Air Force celebrated in groundbreaking ski film

Ski films don’t typically trade in irony. They deal in the obvious risks and rewards of the sport and the sometimes catastrophic consequences – all set to pulse-pounding music. But Jon Klaczkiewicz’s new “Swift. Silent. Deep.” is loaded with irony.

First, the former award-winning Teton Gravity Research producer chose as his vehicle to break out of the “ski porn” industry the story of the Jackson Hole Air Force – a group of hardcore rebels on skis who in many ways founded the big-mountain, extreme culture so celebrated in modern ski films.

Then there’s the fact that the most famous Air Force member of all, Doug Coombs, inadvertently doomed the closely guarded anonymity of the clandestine group by famously having his pass pulled for skiing a closed but unsigned run at Jackson in 1997.

Then there’s the fact that the most famous Air Force member of all, Doug Coombs, inadvertently doomed the closely guarded anonymity of the clandestine group by famously having his pass pulled for skiing a closed but unsigned run at Jackson in 1997.

The ensuing uproar from Jackson’s core skiing community, including petition drives and legal challenges of existing backcountry access laws, led to the resort’s open-gate policy in 1999 and an American backcountry skiing movement that more closely mirrors Europe’s ski-at-your-own-risk leniency.

By then, though, Coombs had taken his steep skiing camps to the more laissez-faire environs of La Grave, France, where he died in a fall off a steep rock band while trying to rescue another skier in 2006.

Coombs cut his teeth on arguably the most intense inbounds – and out-of-bounds – ski mountain in North America, exploring the daunting steeps, chutes and cliffs of early 1980s Jackson Hole with the likes of Dave “The Wave” Muccino, “Sick” Rick Armstrong, Howie “Captain Video” Henderson and the Hunt brothers (Jon and Rick).

But before Coombs even hit the scene, Benny Wilson, whose parents owned the Hostel X next to the Mangy Moose bar in Teton Village, launched the underground Air Force to combat the growing crackdown on renegade skiers.

The conflict came to a head in 1986 when an epic storm cycle dumped more than 14 feet of snow on Jackson and two ski patrollers died in slides in a two-month period. The Forest Service and sheriff’s department turned up the heat, pressuring ski patrol into becoming mountain cops who set traps for rope-cutting skiers, blew up jumps and destroyed Air Force warming huts.

The Air Force countered by monitoring ski patrol radio frequencies and adopting a code of silence emblazoned on their “Swift. Silent. Deep.” membership patches, which could only be quietly bestowed on worthy skiers by an existing member.

“There’re people who keep asking me what happened to the silent part,” Wilson says of the irony of a film publicizing a super-secret band of outlaw skiers. “We weren’t into fame into fortune at all.”

The group’s profile rose meteorically in 1991 when Coombs won the inaugural World Extreme Skiing Championships in Valdez, Alaska, charting first descents by helicopter in the world’s most storied backcountry ski terrain: the Chugach Mountains. Jackson’s Jon Hunt won the second year and Coombs won again in ’93, firmly establishing Alaska’s heli-skiing scene in the process.

“Then when they come back (to Jackson) from a place without boundaries to a place with boundaries, they realized how silly the whole thing was because of the liability issue in the United States,” says Klaczkiewicz, who moved to Jackson the year before the open-gate policy and soon thereafter received his own S.S.D. patch.

He came up with the concept of the film listening to old Air Force stories while waiting in tram lines, and brought in camera operator and cinematographer Peter Pilafian (“Dog Town and Z-Boys”, “Riding Giants”) last winter to begin filming interviews. Much of the old ski footage came from Henderson and includes Coombs voice behind the camera in some shots.

Pilafian says the joy of the sport, devoid of commercial pretention, comes through in the film, and that on-the-edge skiing is now embraced by resorts touting terrain parks and extreme terrain.

“The irony is that it eventually turned around so completely that it’s now a marketing tool,” says Pilafian. “The stuff these guys were getting busted for is now being used to bring more tourists here.”

And for Klaczkiewicz that signals the end of era, with skiing and ski towns increasingly dominated by big money real estate deals and mass marketing. The Jackson Hole Air Force pushed the boundaries so hard there no longer are any boundaries.

“What is a rebel without the thing it rebels against?” Klaczkiewicz asks. “The whole renegade paradigm they’d adopted, the whole Easy Rider mentality is gone.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login