Where has all the snow gone? Colorado snowpack evolving with climate change

With only a couple of months until the 2022-23 ski season kicks off (and far less time until the snow guns crank up), it’s time to start thinking about the only season that really matters in Colorado: Snow season.

Sure, we all love our fall hikes with our dogs – and there will be plenty of those before the snow flies – but what really gets the heart going is the ability to skinny ski or skin up and ski down those same trails with far fewer people and dogs in the way.

For more blogs on dogs, click here.

But if you really want the goods, you’ve got to go in-bounds alpine skiing or bone up on your avalanche safety and get out of the side-country and into the backcountry this season.

Vail recently announced it will open for the season (weather and snowpack permitting) on Friday, Nov. 11, along with fellow Epic Pass resort Breckenridge. Beaver Creek will open on its traditional Wednesday before Thanksgiving on Nov. 23.

Monday, Sept. 5 (aka Labor Day), is supposedly the deadline for buying Epic Passes for the lowest prices ($859 for an unrestricted adult), but I’ve seen these “deadlines” extended in the past to squeeze out some more early-season pass sales.

Also, in the opening dates press release was the announcement that Vail Resorts will limit one-day window sales on some busy ski days to try to get a handle on the crowding issues that gave the company a post-COVID black eye last season.

My take is this won’t do much to solve the problem. Despite years of efforts to spread skiers out across the entire season, they like to come during peak holidays when kids are out of school, and the local and state populations has grown enormously.

The only real solution is to limit Epic Pass users via the COVID reservation system that worked pretty well during the 2021-22 season, because the vast majority of people have figured out a $900 season pass (they used to be twice that when I first moved here in the early 90s) is a hell of a deal. And Vail Resorts has figured out it’s great guaranteed revenue during the off-season.

My guess is very few guests actually buy single-day window tickets (analysis on that here and here), and they’re certainly not the hordes of local or state residents who tend to mack up the majority of the pow.

Figure out how to staff up appropriately (boosting wages, building more housing and increasing local transit) based on the amount of available terrain and cap skier days based on available acreage. That’s the way to rein in crowding.

All of that aside, weather will always throw a wrench in the best-laid plans, and weather is likely becoming tougher and tougher to predict due to manmade climate change.

Go-to meteorology and powder predictor site Opensnow.com on Aug. 23 posted about the possibility of triple-dip La Niña this coming season, with lower sea temperatures and possibly above-average snow compared to the last two rather anemic La Niñas.

“A La Niña pattern has persisted into the summer of 2022, and long-range models have been projecting a higher than average chance of a La Niña continuing into the winter of 2022-2023, before possibly weakening in the spring of 2023,” Opensnow.com meteorologist Sam Collentine wrote. The recent dry and hot spell into early September notwithstanding.

Collentine’s post included this rather enticing comparison to the heavy 2010-11 La Niña season that led to Vail’s all-time record 525-inch ski season.

“The effects of La Niña appear to show much of the Western US receiving average to above-average snowfall during these significant events. Again, though, the pattern doesn’t hold 100% of the time,” he wrote.

More recently, however, Opensnow.com also shared and analyzed NOAA’s 2022-23 winter forecast, pointing out how generally unreliable long-range forecasts can be.

All of which is to say, the coming season could be good, could be bad, or most likely will be somewhere in-between. Bottom line is we are trending down on our snowpack numbers due to climate change, shrinking the length of ski seasons, causing mid-season melting and massively impacting our local rivers.

For the 2021-22 winter issue of Vail Valley Magazine, I wrote the following article on how our snowpack is changing and what it means for the sports we all love and the forests that surround us. Bear in mind, this was written about this time last year. Enjoy.

Where Has All the Snow Gone?

Climate crisis hits home in Colorado ski towns

Kim Schlaepfer of the Walking Mountain Science Center in Avon isn’t just the project manager for the local Climate Action Collaborative that’s working feverishly to achieve a 50% greenhouse gas reduction in Eagle County by 2030 and an 80% reduction by 2050, she’s also an avid skier who loves to be outdoors as much as humanly possible.

As such, she reached for two different stories when asked for anecdotal evidence of how climate change is impacting outdoor recreation in the Vail Valley, both of which, she says, “fit the bill for the new climate future perfectly.”

The first example was a date that shall live in Vail infamy: Feb. 7, 2020. That was when 38 inches of heavy, windblown snow fell in 48 hours, leading to avalanche closures, transportation snarls and massive lift lines dubbed “Snowpocalypse”. It was early in one of Colorado’s typically coldest months, and yet the snow was far from Colorado “champagne” powder.

“There was so much snow, that it was too much snow,” Schlaepfer remembers. “Not only that but the snow had drifted in odd ways to be six feet deep in some areas and only one foot in others. It made skiing that day a complete mess, and most of the day was spent digging out of snow holes. It was not a fun powder day that we all know and love, but rather a day spent battling the mountain and skiing in other people’s lines so you didn’t get stuck.”

So what does the overabundance of Snowpocalypse’s heavy pasting have to do with manmade climate change and a world the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reports has seen a 1.5 degree Fahrenheit overall temperature increase since the decade before Vail first cranked up its lifts in 1962 (and two full degrees since pre-industrial times)?

“Climate studies [predict] we will have fewer smaller storms and larger storm events that will drop a lot of precipitation. Storms like this — that seem good but behave in ways we are unfamiliar with — are a warning sign of the change we’re in for,” Schlaepfer says. Just the previous spring, in March of 2019, a “bomb cyclone” of heavy, wet snow crashed into Colorado, paralyzing the state’s Front Range and sending historically large avalanches down onto Interstate 70 in Summit and Eagle counties.

Brian Lazar, deputy director of the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, said at the time that the bigger, “juicier” storms that season were consistent “with predictions of a warmer climate. That warm air can kind of just hold more moisture. Colorado is typically colder and drier, but if the air over Colorado were to get warmer, it can produce wetter storms.”

Then there’s the opposite but related end of the spectrum: warmer, drier springs and summers that are leading to more intense wildfires. A recent U.S. Geological Survey study found that flows in the Upper Colorado River Basin, which includes the Eagle River, have decreased by 20% over the last century, much of that owing to declining snow cover and increased evaporation. Researchers at Colorado State University have predicted flows in the Colorado River, which supports 40 million people, could decrease by another 30% by the middle of this century, owing primarily to warming and lost snowpack.

“The second anecdotal evidence I can share is the smoke from the fires this summer,” Walking Mountains’ Schlaepfer adds. “Smoke affected our communities’ health in unexpected ways, and made going outside to do activities daunting. I think this is going to be somewhat of a new normal for the American West as we grapple with hotter temperatures and less precipitation.”

The 2019-20 ski season in Vail, including Snowpocalypse, came to an abrupt end about a month later when the global COVID-19 pandemic arrived on airplanes from around the world. Despite that huge February dump, when the lifts improbably shut down at the height of spring break in mid March, Vail was on track for a fairly average snow season of around 330 cumulative inches, or about 28 feet of snow. Last season (2020-21) wound up well off that pace, with Vail closing in a more normal fashion (no abrupt, health-related shutdown) at 233 inches and Beaver Creek just behind at 232 – a full 100 inches below seasonal averages.

Dr. Keith Musselman, a member of Protect Our Winter’s Science Alliance, has a day job that keeps him at the forefront of studying the aridification of Colorado as a result of climate change. A hydrologist at the University of Colorado, he has closely documented how mountain snowpack is tied to sustainable forests and water supplies, but he’s also an avid skier, snowboarder and surfer who transplanted from the East Coast in part to ride snow in Colorado.

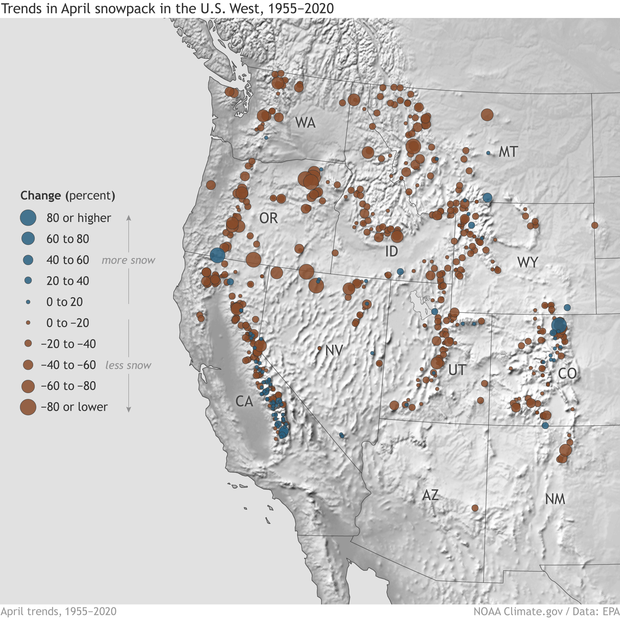

“Global greenhouse gas emissions pose a direct threat to Colorado ski towns from many angles ranging from diminished snowpack, greater reliance on energy-intensive snowmaking using increasingly restricted water resources, and warming and drought enhanced wildfires that broadly affect mountain communities,” Musselman says, citing a paper he published in 2021 that looked historically at 1,065 snow monitoring stations across western North American – many of them in Colorado.

Published in Nature Climate Change journal, the study showed only about 11% of the stations with declining snowpack (snow water equivalent) since the mid-20th century, but more than three times that percentage of stations showed increased winter snowmelt. “Thus, continental-scale snow water resources are in steeper decline than inferred from [snow water equivalent] trends alone. More winter snowmelt will complicate future water resource planning and management,” his study concludes.

Colorado’s mountain snowpack serves as a water-storage system that in years past slowly released its bounty into streams, lakes and reservoirs after first recharging soils. Earlier winter snowmelt, Musselman says, “is a sign that warming is starting to chip away at Colorado’s climate resiliency.”

Citing the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Musselman says it’s well-established that summers are getting hotter due to climate change, which means more evaporation from the soils, less water available for ecosystems, including plants and trees, and a drier landscape that can actually reduce summertime rainfall and cause drier thunderstorms.

“As snowpack melts out earlier in response to warming and/or drought, streamflow and soil moisture will follow suit, setting the stage for more arid conditions that are prone to more frequent and larger wildfires,” Musselman says. “Our state’s large fires are incidentally burning in the same headwater forests that harbor our deep snowpack and much of our water resources.”

The summer of 2020 saw the three largest wildfires in Colorado history and also the largest in the history of White River National Forest that surrounds Vail. That blaze, the Grizzly Creek Fire, incinerated much of the vegetation that secures the rocks and soils making up the steep sides of Glenwood Canyon. While the summer of 2021 wasn’t as bad of a fire season as 2020 in Colorado, it did include a big blaze in western Eagle County above Sylvan Lake and then torrential monsoonal flow that scoured Glenwood Canyon, causing mud and rock slides that shut down Interstate 70 for weeks. Transportation snarls aside, the local Sylvan blaze and massive fires in California fouled the formerly cobalt-blue Colorado skies for months.

Auden Schendler is a climate activist and senior vice president of sustainability at Aspen Skiing Company, but he’s also served on the board of Protect Our Winters and as a town council member in Basalt, in southwestern Eagle County, where a wildfire nearly destroyed the town in 2018. His anecdotal evidence of the impacts of climate change is rather obvious.

“We’re seeing measurable changes like warmer temperatures, earlier runoff, and shockingly, a month fewer days with frost since a hundred years ago,” Schendler says. “And I had always thought about climate and skiing as a heat and lack of snow problem, but in the last few summers I watched my hometown almost burn down, and then I-70 burn and close, and this summer you saw Sierra resorts turning snow guns on in the summer to prevent incineration. If you look at the forests around us, they are dry and widely dying. So, to me, the presenting threat is fire, and the consequence of fire is not just that you might burn down, but if you survive, you then have mudslides, river and fishery destruction, invasive weed infestation … and I think those changes we’re seeing in real time are going to get us before it’s too hot to ski.”

Clearly the whole globe needs to take action, but what can the ski and outdoor industry do to help save our beloved ski towns from the worst effects of climate change before it’s too late?

“To me, the infrastructure changes we need to make are the ones that solve the climate crisis,” Schendler says. “Fixing climate would mean a renewable energy grid, grid improvements and smart-grid development, electrification of transportation, industry and housing, and then urban planning that makes climate sense, among about a thousand other things. Adapting to what we’re headed for isn’t plausible, but measures in the mountains changing building codes so they’re more energy efficient and fire and flood resistant kills two birds with one stone. We’re going to have to really manage forests, especially in the urban interface and around transportation corridors.”

POW’s Musselman says “the single most urgent infrastructure change is reducing emissions that are result of air travel tied to the success of our resort towns.” Aircraft may account for 25% of the global carbon budget by 2050 as emissions from other sectors successfully phase out reliance on fossil fuels, according to the 2019 United Nations report from the International Civil Aviation Organization.

“This is incredibly urgent in terms of direct impact, but distant in terms of viable technological solutions,” Musselman says, but he adds rapid changes to Colorado’s ground transportation sector are nearly as urgent because the I-70 corridor is a huge source of greenhouse gasses and other pollutants. “We can’t afford to continue to widen our highways to make room for more cars and reduce our perception of congestion. The transportation emissions issues – its contribution to global climate change – needs to be addressed at its root and may require a re-envisioning of how Coloradans will travel later this century.”

A recent Rocky Mountain Climate Organization report estimates the average number of days 85 degrees Fahrenheit or warmer in the Avon/Edwards area will increase to 16 by mid-century compared to just one a year from 1970 to 1999 and could go as high as 43 in the hottest years. By far the biggest producer of greenhouse gas emissions in Eagle County, according to the Climate Action Collaborative (CAC), is the transportation sector at 509,480 metric tons of CO2 a year.

CAC’s Schlaepfer cites advocacy to government officials for policy changes as the number one thing individuals and organizations can do to combat climate change, but then she points to the need for a better and more reliable public transportation system and more connected communities. She adds that electric vehicles (EV’s) are a good way to cut emissions but come with their own host of issues for the climate, from lithium mining to battery recycling.

“We are a community that has a car-centric culture and that will be impossible to change if we don’t start building our communities so walking, biking, and public transportation are the easiest and most reliable options to get from point A to point B,” Schlaepfer says. Eagle County has been in talks with Avon, Vail, Eagle and other towns to form a regional transit authority to more rapidly electrify and build out public transportation throughout the county, and Vail – already with one of the largest free bus systems in the nation – recently signed a resolution to switch all of its vehicles to zero emissions under GoEV City.

Paul Chinowsky, director of the Program in Environmental Design and a professor of civil, environmental and architectural engineering at the University of Colorado Boulder, contributed to a UN IPCC report on the adaption and vulnerability of infrastructure as climate change intensifies. He also moved to Colorado two decades ago in part to ski powder.

“The biggest change that is needed is a move to renewable energy,” Chinowsky says. “I know that many resorts are already moving in this direction, but we are still a fossil-fuel based economy and that is the biggest impact on climate change. And the fact is that while the resort itself may be moving to greener energy, they rely on tourists who are staying in hotels, driving [gas-powered] vehicles to the resorts, eating at restaurants, etcetera. So, a push to renewable energy and upgrading that infrastructure is the biggest need. We are not going to stop people from driving to the resorts, so we need to change the energy source that allows these successful visits to occur.”

Since 2010, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration, Colorado has transitioned from a nearly 70% coal-fired power state to just 36% in 2020. Renewable sources of electricity such as wind, solar and hydro have jumped up to 30%, with most of the other 25% coming from natural gas. That still makes Colorado a nearly 60% fossil-fuel-powered state, although natural gas burns about 50% cleaner than coal.

Schlaepfer calls transitioning the power sector the low-hanging fruit of reducing emissions, while the transportation and to some degree building sectors will require sweeping policy changes and a voluntary shift in human behavior – something that’s far more difficult to achieve.

Chinowsky adds that current ridesharing incentives to the slopes won’t really make a dent is decreasing emissions from the transportation sector, but the ski and outdoor recreation industry could be a bigger force for change by pushing even harder for state and federal subsidies for EV’s. Many are in place already, but he argues they can and should be much more robust.

“I know that many people hate subsidies, but the fact is that we need to change the vehicles that people are driving in to eventually reduce emissions,” Chinowsky says. “I also think that outdoor and ski companies need to get on an incentivization push to encourage people who drive in EV’s or ride share. Not just free parking, but really think about creative ways to attract people such as a discounted ticket, or discounted food, or something that is a tangible benefit. Outdoor sports are expensive – people will only change their behavior if the incentive matches the scope of the activity.”

As for advocacy, Aspen’s Schendler, who has been out front for years on the need for dramatic climate policies, testifying before Congress and writing op/eds in The New York Times, was pleased to see the announcement this summer from a slew of ski companies forming the Climate Collaborative. Made up of Vail Resorts, Alterra, Boyne and Powdr, it pledges that “climate change is the most critical issue ski resort companies face as business leaders and as citizens of this continent and inhabitants of earth.” It also comes with a host of action items, including advocacy, where Schendler would like to see more intensity.

“The reconciliation bill is widely understood to be the last chance for American climate policy,” he says. “There should be a full court press there. Really noisy, done in a way you can’t avoid. Heads of trade groups. CEOs. Op eds. That is not happening.”

Kate Wilson, Vail Resorts sustainability director, says the company has been pushing for policy changes since well before the new Climate Collaborative.

“One example is our annual participation in LEAD on Climate, a group of over 330 businesses lobbying lawmakers in D.C. to build climate solutions into potential infrastructure packages,” Wilson says. “We also publicly disagreed with the Trump Administration for its decision to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris climate agreement, and in April 2021, we joined over 400 U.S. companies in asking the Biden Administration to commit the U.S. to an emissions reductions target of at least 50% by 2030, which they then did.”

But advocacy alone won’t solve the problem, Wilson adds.

“We have known for a very long time that advocacy is only one pillar of the fight against climate change,” she says. “As a leader we know it’s important to stand up and use our voice, but we also know it’s important to lead with action – that’s why we focus so much on our Commitment to Zero.”

Announced in 2017, Vail Resorts’ Commitment to Zero targets a zero net operating footprint by 2030 for all 37 VR resorts in 15 states and three countries through its three pillars of zero net emissions, zero waste to landfills and zero net operating impact on forests and habitat.

“Due to recent investments in solar and wind energy, we’re on track to achieve 90 percent renewable electricity across our resorts by 2023,” Wilson says. “As a company, our approach has been that if you’re not setting goals so big you’re not initially sure how you’ll reach them, they’re not big enough to solve climate change.”

Latest posts by David O. Williams (see all)

- Democratization or ruination? A deep dive on impacts of multi-resort ski passes on ski towns - February 5, 2025

- Western Rail Coalition looks to revive passenger rail service on long-dormant line connecting Colorado mountain towns - January 22, 2025

- Colorado ski town looks to dig deep, diversify energy sources as climate change threat looms - January 10, 2025

You must be logged in to post a comment Login